CLICK HERE FOR THE ENGLISH VERSION

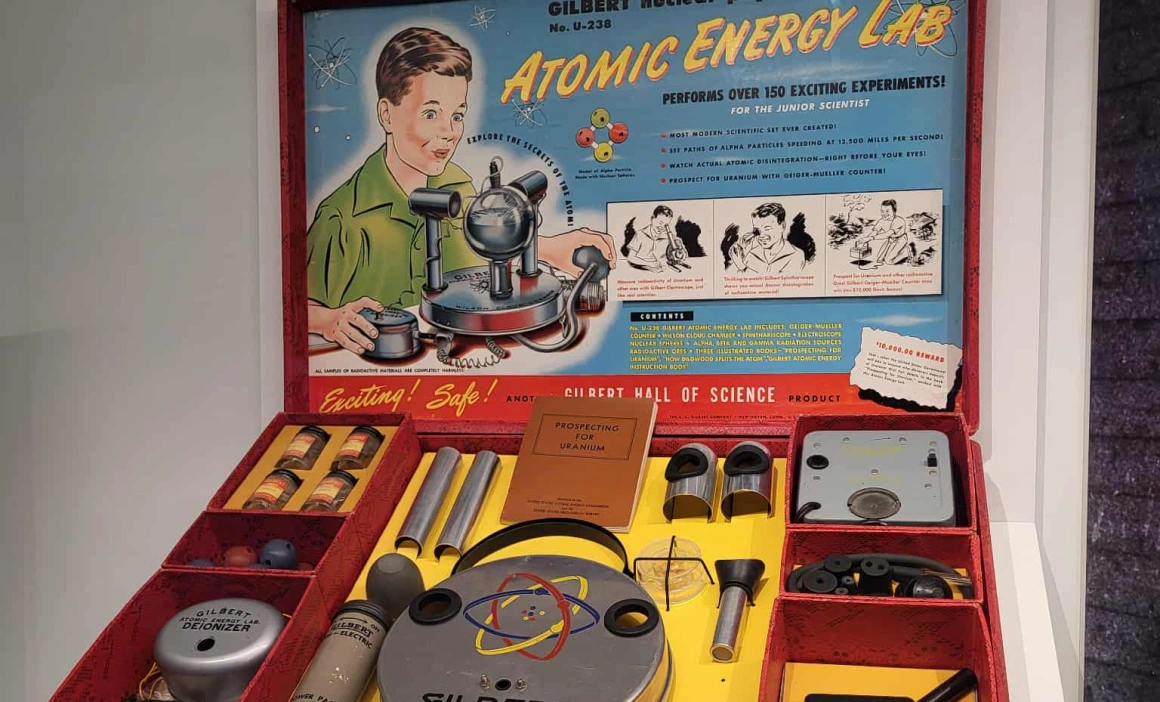

Online challenges, real-life consequences. After looking at Romania and its media education programs, I set out on a global map in search of prevention initiatives. I reached France, Brazil, and the USA. With a stopover in Germany. During the summer, the Munich Museum of Technology serves as a daily air-conditioned refuge for 3,800 tourists. I stop in front of a red box containing chemistry instruments—the "Atomic Energy Lab." "Exciting! Safe!" is written on one corner. Created in 1950 by a US company, the game allowed children to create small nuclear and chemical reactions at home. It contained uranium samples, a Geiger-Muller radiation counter, and a comic book written in collaboration with General Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project—the WWII US program that created the atomic bombs. The game was launched five years after the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Cynical? What’s the deal with this game? Was it truly "safe"? Experts say that although the radiation level in the beautiful red box is low, it’s not a good idea for it to be around children for long. The game didn't fail because it was dangerous, but because it was too expensive—the $49.50 from 75 years ago would be over $500 in today's money. These chemistry kits were super trendy back then, despite containing a slew of substances that today would only be acceptable on the Dark Web. It took about 30 years and various regulations before the American state banned dangerous substances in toys. How long will it take us with social networks? Are social networks a game with uranium? Yes and no. An online survey among 13- to 15-year-olds, parents, and teachers worldwide shows that the last challenge they encountered was funny for 48% of participants, 32% said it presented a risk, 14% said it presented a risk and was dangerous, and 3% said the challenge they saw was truly dangerous. How many actually participated in them? 21% overall, of which 0.3% in extremely dangerous ones. Few. Except that the dangerous ones can have terrible health effects on those who try them or can even be fatal. For these, I found solutions in France, Brazil, and the USA, where parent organizations, after losing their children to such a "game," have developed education and prevention programs that yield results. Françoise Cochet shook off her grief to understand what the policeman was trying to tell her after the death of her 14-year-old son, Nicolas. "He told us it wasn't the first death because of that game," she recalls now. Her first thought was to alert others about "le jeu du foulard"—the "scarf game." It had many names and forms and had been circulating among teenagers as a challenge for years. It was the 2000s. She began writing to all the press. "The scarf game, testimonies are pouring in," wrote Nice Matin a month after the tragedy. In March 2001, Le Figaro put the subject on its front page: "Teenagers in Danger. Deadly Game," featuring the faces of eight teenagers who had lost their lives in the last five years. Françoise went to the Ministry of Education and Health, but nothing seemed to move toward prevention. So, together with several families, she founded APEAS—the Association of Parents of Children Injured by Strangulation (Association de parents d'enfants accidentés par strangulation)—and started an educational program to bring into schools. First for parents and teachers, then for children. Every year, more parents who had gone through this came to them to understand more. Françoise tells me the story alongside Julien Serot, a parent who lost his son a year ago and who, while grieving, discovered the association. "Gabriel had had a normal day, a happy day, everything was fine. So it took us about a week after his funeral to realize what happened, to truly understand what he did." He found Françoise's association online and decided to get involved. "It is a tragedy, but there is also a little hope at the same time. We also have a daughter who is two years younger, and we must do this for her and for every child," he says. Despite APEAS's efforts, French authorities have not begun quantifying cases as accidents resulting from dangerous games or challenges. "They say there are zero cases because in police and gendarmerie files, it is noted as either suicide or a domestic accident, and it is impossible to fill in 'dangerous game,'" Françoise explains. But they managed to convince researchers to study the phenomenon. In 2015, a questionnaire conducted in a school in Toulouse revealed that 40% of students had tried the "asphyxiation game." A descriptive study involving 246 children showed that 1 in 4 had tried the "choking game," "space monkey," or "blackout" and other names it had taken. So they did everything possible to take their workshops to children through parent associations. "We believe there is only one correct way to explain it to children, and that is to see what happens in their bodies if they don't have oxygen. When they receive a very physiological explanation, in their own words, they no longer want to try. They understand and don't want to be hurt. We don't talk about death with them," says Françoise. In the two hours I spoke with Françoise and Julien, I could have grazed through over a thousand social media clips. In the four months I spent documenting and writing this article, over 2.1 billion videos were uploaded to TikTok and 1.5 billion to YouTube. How do these two parents see the unequal struggle with social networks? We are, after all, talking about France, a country that has so far had several initiatives for the online safety of children and adolescents: "My son had a brand-new phone bought a month before his death, and he didn't have social media. So maybe he saw a video on a friend's phone. Before smartphones, children had to wait for holidays to meet their cousins from another city. Today, you can have a new challenge go viral from Paris to Marseille in half an hour," Julien believes. "From Paris to Marseille," from one country to another. When Françoise organized the first conference with experts on the topic of dangerous games in 2014, she had participants from other countries, like Brazil or the USA. I try to make some mental space after the discussion with Françoise and Julien. Now billions of eyes are watching millions of small "TV stations." I open my phone, being generous with myself, and choose 5 minutes of Instagram (I use an app that helps me spend less time on social networks). Among the first clips I see is one posted by Smartphone Free Childhood US. A child is ready for bed, in his bed, and the father, before "good night," presents the things from the internet: pornography, classmates' meanness, prohibited substances, scammers. They are all now in the children's room, a click away. "Try to ignore them, okay?" the father says and closes the door. "We ask too much of children when we give them a smartphone," is the clip's message. The bedroom is no longer the safest place for children, Fabiola Vasconcelos, a psychologist at the Instituto DimiCuida in Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil, tells me. "Parents believe that if they are at home, the child is safe. 'They don't like to go out at night. They don't go out Saturday night with friends. They're safe.' It's no longer true. It wasn't even in the old days, let alone now." We break the ice in our Meet discussion—she in the early morning, I toward the end of the day—talking about her large ring with a black stone made by a Brazilian designer. We also talk about how big Brazil is, with a population of 213 million, 10 times that of Romania. Organized into 26 states and a federal district, each with its own government and constitution. We delve into the history of the institute she works for, which bears the name of Dimi, a 16-year-old boy who died in 2014 after trying such an asphyxiation challenge. "He was born into a wealthy family and was well cared for. His parents were married, he had siblings, and he was the youngest. He was educated at one of the best schools in the city. He liked skateboarding. He loved technology and his dream was even to pursue a career in science," the psychologist describes him. When they investigated the case, authorities discovered "that he was experimenting with two different types of dangerous behaviors or challenges. We didn't know how widespread it was; we only knew it was called the 'pass out challenge.'" Dimi's parents began searching for information, and since there was nothing about it in Brazil, they ended up at the conference in France organized by Françoise Cochet. There they also learned about Erik’s Cause, an initiative started following the death of Judy Rogg's son in California, whom I would also meet. "What can connect a teenager from northeast Brazil, with a 12-year-old from northern California and a 14-year-old boy from France who all died because of the exact same challenge?" they wondered. The following year, they held a first symposium in Brazil that brought together over 300 people from education, law, safety, health, and parents for two days. They organized into three committees: From the first research they conducted in 2015, it emerged that 1 in 4 children had tried a dangerous challenge. From here, they began alerting parents and teachers. "We now have many children who have a digital life, which is not unreal to them; it is very real, they believe they truly exist in this environment. It is a period when they have the curiosity to challenge their bodies, and even this boundary between life and death is a very curious subject for them," the psychologist explains. The DimiCuida Institute found from research that most accidents occurred between the ages of 11 and 13. They also discovered that most dangerous content was created by adults. "'I set myself on fire and jump into water,' 'I'm going to drink everything blue in the house,' 'I'm going to staple my tongue,' 'I'm going to super-glue my lips.' All are available on YouTube. This is the content of our main challenger who has about 16 million followers in Brazil," says Fabiola Vasconcelos. What she describes is valid everywhere in the world, including here. In fact, MrBeast, who in November this year became the YouTuber with the most subscribers, started the same way, with challenges. Ilie Bivol was among the first influencers here who sparked thousands of reactions with his challenges ten years ago. When she meets parents, she asks if they have heard of this influencer. Most have no clue. What the Brazilian psychologist says, however, is that it is no longer so simple for you as an adult to reach this content. "A very dangerous space is gaming platforms where developers do not filter users. If you are not invited into a Discord community, you don't know what's happening inside. So, we have a new area to worry about, spaces where parents are not present at all." Simultaneously, they went into schools and organized prevention meetings with parents, and trained teachers throughout the state of Ceará. For years, in Fortaleza, a city of 3 million inhabitants, they had no more fatal accidents. Until 2022. Then an 8-year-old child died. They had targeted the over-9 age group in their programs. The last fatal case was this year, an 8-year-old girl. "This pushed the entire government and a large number of institutions, including us, to say that we need laws, we need regulation, we need something that truly protects parents and children." So Brazil is currently working on legislation to regulate the age of entry onto platforms and heavy fines for companies that do not verify minor users. "And our main debate right now is how we can have age verification that doesn't extract data from children and keep it somewhere," the psychologist explains. The concern is also valid for the digital age of majority law here—that it would burden the state with bureaucracy and lead to "excessive collection of personal data," as Bogdan Manolea, president of the Association for Technology and Internet, told Free Europe. So far, only in Australia have they found the solution to identify teenagers by likes and preferences, exactly how they identified them to deliver ads. Because the work week in Brazil is 44 hours, many people work six days, while the school week is five days. So the right place for prevention remains the school, Fabiola believes, through programs that emphasize developing skills such as conflict resolution, "a discipline like mathematics, languages, or sciences." "We know from neuroscience that to make analytical choices, to recognize right from wrong, the prefrontal cortex must be fully developed, which happens at age 24-25. So, if you ask a 9-year-old to have the analytical skills to evaluate and make the right decision, we are asking for something impossible. What we can train earlier is this ability that makes our children stop and think." The scientific explanation of what happens in your body if you deprive it of oxygen works. "One thing that truly scares them is when we explain that once your body is deprived of oxygen, sphincter control is lost. It scares them to end up in an embarrassing moment with friends present," Fabiola says. And very importantly: "If you tell children 'don't do that,' it's more of an invitation to try. But if I ask them 'what do you think about this?', we start a discussion. And teenagers want to be heard. A lot of behaviors stem from not feeling seen and heard." Judy Rogg immediately enters trainer mode and presents to me how the course they developed should be taught. We quickly arrive at what Fabiola said—the ick factor, that disgust factor to which children and adolescents react more strongly than to "don't do that or you'll die!" "'What happens when the brain loses oxygen?' we ask them. We let them answer, and then we tell them various things that can happen. Remember you are dealing with children; if they haven't had someone in the family who had a heart attack or a stroke, they are unlikely to know. We stop at two issues: one is retinal hemorrhage, the second is loss of control of bodily functions, meaning you can urinate or defecate. The disgust factors reach them more than the idea of a stroke or a heart attack." Judy is in her home in California; strong sunlight streams through her living room window. In Bucharest, it's almost midnight. She sneezes occasionally and apologizes: "It's allergy season." She goes through each slide and insists that when you are in front of children, you must have a dialogue. What do you do when a student asks you exactly how these challenges are carried out? I challenge her. "We tell them again that it is an interruption of oxygen and blood to the brain. Because by telling them how it's done, we are telling them how to do it. And that is not our intention. And if they continue to talk about it, we just tell them that we will discuss it separately at the end." Judy is 73 years old and still works part-time as a psychiatric nurse. But her main job is at Erik’s Cause, the NGO she founded immediately after the death of her son Erik in 2010 following a choking game. "I was a single mother, I am not married. I am no longer young and I was a mother at a late age. This is Erik's legacy. Even if things go slowly, I simply cannot stop," she tells me. Fifteen years ago, she had no clue about this challenge either. She quickly understood she had to do something to prevent it and first went to her son's school. "There were a few other programs at that time, but they were very graphic, very explicit. They told me if I could do something that isn't traumatizing, based on skill acquisition, they would use it." The program was piloted by Erik's teacher in seventh grade. Then it was to be expanded to another school, but a parent opposed it and it all stopped. When one door closed, she decided to go elsewhere. She reached Iron County, Utah, a town of 30,000 people. "They had had four teenage deaths from this choking game in five years." The detective who investigated the cases understood what had happened and, looking for solutions, came across Erik’s Cause. Their course was incorporated into health classes in fifth, seventh, and tenth grades. This was 2012-2013. "They had no more deaths and, no longer being recent news, after a while they wondered why they were still doing this, and two years ago they stopped holding these courses. We are here if they need us again," Judy says understandingly. In fact, being able to do this in schools formally was the main barrier to their program. They sought other options: parent assemblies, parent-child evenings, courses for parents and teachers. They expanded their course to other themes: cyberbullying, sexting, revenge porn, substance use. All their courses take into account the "window of tolerance." "It is the bandwidth in which you can receive information and assimilate it, whether as a child or an adult. If you introduce something traumatizing—it could be an event, a photo, screams in a 911 call—these are things that can shock the person and take them outside the window of tolerance. And once that happens, they won't be able to absorb the information," Judy explains. For example, they show them a brain divided into several compartments labeled: love lobe, TV archive, social media addiction, love for parents, hatred for parents, ego, weirdness, rebellion center on super turbo. This is the part with maximum fun. "If we take the teenage brain and add social media, here's what happens. And they see a drawing of a boy skydiving, but instead of being concerned with opening it, he's taking a selfie. Again, you make them laugh, but they learn about something serious." Then they are shown what it means when the brain no longer receives blood and oxygen—a hose whose water jet is stopped. They then talk about how the internet and its algorithms work, about manipulation. Finally, they see a video with the faces of hundreds of children who lost their lives. Sometimes children tell her this part is boring. "It is still emotional and powerful to see these children who could be their classmates, friends, or sports teammates." In their program, they teach through examples but challenge them to come up with ideas on how they could escape the pressure to do something they don't want to, how to say no. "But you can use your parents' help, make a secret code with them for when to call you or come pick you up. It's a little white lie. One child once said he has coded emojis with his parents. Smart move!" I was reminded of the prevention campaigns here. "Selfies on trains take lives, not likes" is written on posters in Bucharest North Station. Then there are school meetings between students and police officers who present the dangers and tell them not to do that. What Françoise, Fabiola, and Judy kept explaining to me is that this type of "don't do that!" information and catastrophic scenarios do not reach teenagers. Those that accept there is this almost natural attraction toward danger and offer them concrete ways to react can have a chance. Judy Rogg believes the next step is to move toward legislation. Regulation is needed. In 2015, there were 202,000 videos of the pass out challenge on YouTube; in 2018, there were already 2.8 million. Tens of millions today. "In a hearing, Senator Marsha Blackburn asked Mark Zuckerberg, what is the life of a child worth to him? From Meta documents, it appears to be $270," Judy says. She is referring to an internal Meta document released by a whistleblower, stating that each teenage user has a commercial value to the company of $270. Judy hopes that all revelations about the knowing manipulation of children by big tech companies will change legislation. One of the laws in the process of adoption—the Kids Online Safety Act—would force big platforms to prevent and moderate any harmful content (sexual exploitation, eating disorders, violent content, or content that could promote suicide), but also to take down and no longer allow addictive content. In addition, users would have the option to no longer allow algorithmic personalization of content. It passed the US Senate, didn't pass the House of Representatives, but has now been reintroduced into the approval circuit after new revelations. European legislation in progress has similar provisions, shaped by the principle of the "best interest of the child" around which platform design should gravitate: taking down harmful or sexual content, no targeted ads, minimum age of 16 (with the possibility for member countries to lower it to 13 if they wish). Several organizations, including Erik’s Cause, have allied to support stricter regulations. "Yes, they have money, yes, they can do what they want, but it depends on us to stop them!" Judy says. She wants all their knowledge so far and the educational program to reach Romania as well. It is free, and they can also offer training for those who want to learn more. Best Practices from Programs in France, Brazil, and the USA: Researchers have conducted meta-analyses on what works in prevention programs for children and youth, looking at substance abuse prevention, sex education, school dropout, and bullying programs. The good ingredients:

How dangerous challenges are combated in France, Brazil, and the USA

The Uranium Game

Nicolas

Dimi

Erik

From Schools to the US Senate

The Science of Prevention